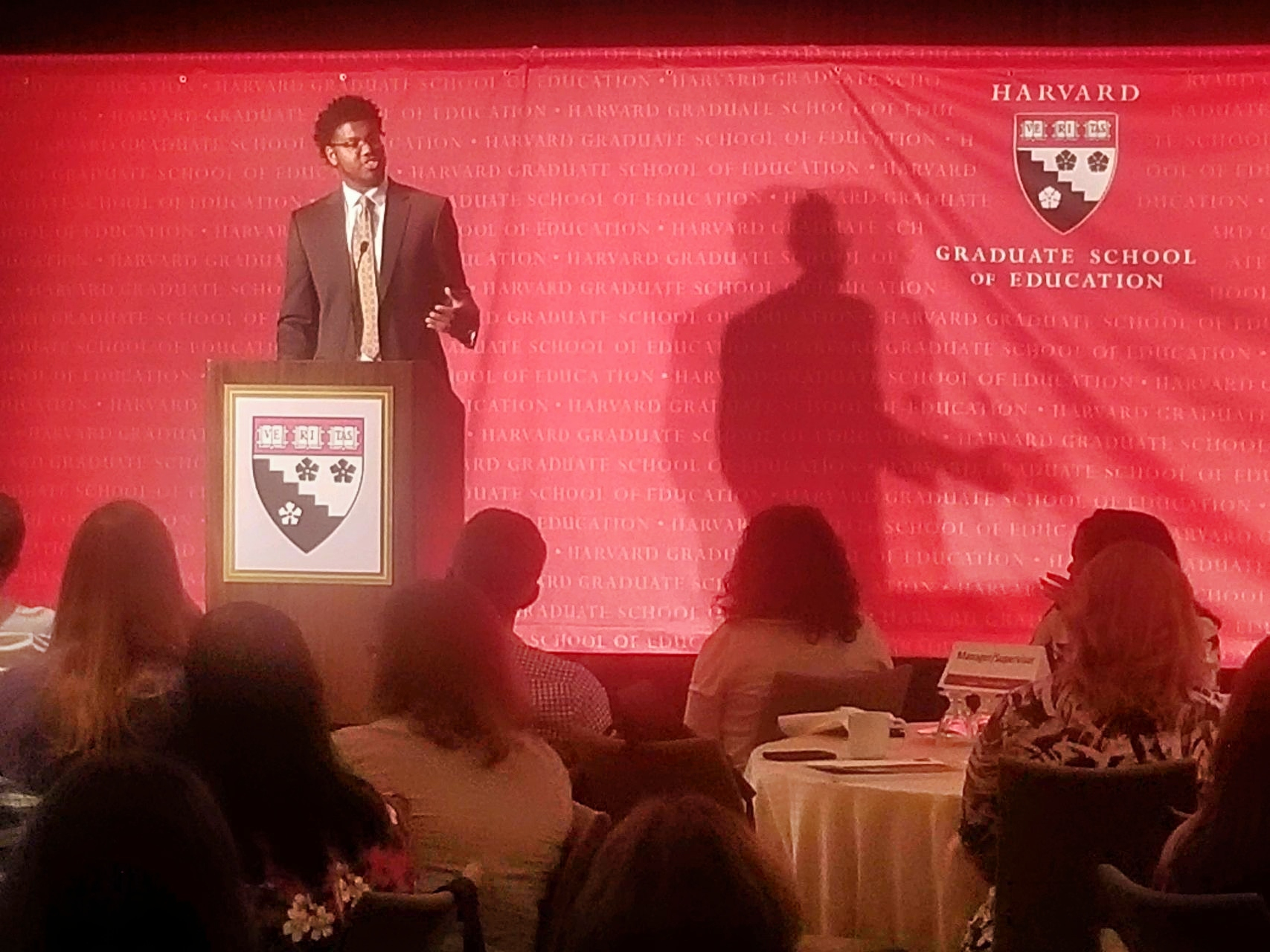

EdTalk delivered by Atnre Alleyne at the Strategic Data Project annual conference in 2019

It’s great to be here today. My journey to this room has been a unique one and I imagine each of us has a unique story of how we came to spend our lives focused on improving the education system. But as I share some of my experiences, I’m sure you’ll find some similarities with your story.

It feels like it was only yesterday that I was a Harvard Strategic Data Project fellow at the Delaware Department of Education.

It feels like only yesterday that I was reading Ho and Castellano and discussing the difference between Gain-based models, conditional status models, and multivariate models for teacher evaluation. (I’m going to quiz some of you later.)

It feels like only yesterday that we were discussing SLOs and SGOs and the validity and reliability of Delaware’s 200+ teacher evaluation assessments.

It was just a few years ago that I was in hours of meetings trying to negotiate more flexibility for administrators to use unannounced observations and trying to get regulations passed that allowed for the use of peer observers.

It hasn’t been that long since we were trying to decide the right amount of money for our retention bonuses for highly-effective educators in high poverty schools. Or the time when we were determining the weights and cuts scores for our new teacher preparation report cards. Or the time when we were discussing whether the PPAT or the edTPA was the right performance assessment.

Things were certainly bumpy but it seemed we made so much progress in such a short period of time. How can you lose when you have such strong logic, research, and data on your side!?

In Delaware, in your states, and across the country we’ve certainly secured significant wins as a result of our research and policies.

But what I want to contend today is that the next frontier of this work and the sustainability of our efforts will require that we flex a different muscle.

What I want to suggest is that the next frontier is going to require that we get out of our heads and start leading with our hearts. That we move beyond the technical to the emotional.

Speaking of hearts and emotion…let me tell you a little bit about my parents.

I’m the last of my mother’s 5 kids, she had me at 40 years old, and she named me Atnreakn Siahyonkron Babatunde Alleyne. Atnreakn is an ancient Egyptian name derived from Akhenaten—the first pharaoh to

institute monotheism. My mother is deep.

My mom is super strong-willed and when I graduated from middle school my mother exercised what I like to call “school choice on steroids.” She shipped me to a military-style boarding school in Accra, Ghana at the ripe age of 13. Somehow the fact that I had never left the country before didn’t change her mind. Nor did my grandmother and my older siblings’ anger dampen her resolve. In December 1998, like it or

not I was on a 13-hour flight from John F Kennedy Airport in NY to Kotoka International Airport in Ghana with a large bag of Skittles to comfort me. You see…my mother is certainly a person of high intellect

but what is instructive about her is that she often knows the right times to follow her heart.

Now let me tell you a bit about my father. My father was an educator and a musician and he died of cancer when I was 6. One of the phrases he always said has stuck with me. With his cool Trinidadian accent he would say: “All who can’t hear must feel.”

If you’re not sure what that means…..at times it meant a spanking was on the horizon. At other times it was a final opportunity to demonstrate I could be guided by reason and intellect instead of my distaste for the feeling of a hand on my rear end. Ultimately, it was an aphorism with a message applicable to all ages: If you don’t listen you will suffer consequences.

My father’s phrase has undoubtedly spared me many mishaps. But taken to it’s extremes it leaves us one-sided and lopsided. And I’d argue that what we have created in our schools AND — in our movement to improve our schools — is an overemphasis on logic and rules and a de-emphasis on feeling and emotion.

Now what does this technocratic, emotionless approach look like in practice?

At times, it manifests itself as a lack of urgency about improving school quality as ultimately we aren’t the ones—or our children— whose potential is being shortchanged by subpar education.

I recently invited several of the parent advocates I worked with to a conference attended mostly by folks working in education nonprofits and advocacy organizations.

During one panel, one of our parent advocates asked everyone in the room to raise their hand if they live in neighborhoods where their feeder school would be considered low-performing.

She then proceeded to define low performing as less than 25 percent of students proficient in Math or Reading. She was the only person with her arm raised in the room.

She later shared with me how much she enjoyed the content of the conference but how she was struck by the lack of emotion and energy about the important work we are doing.

Our lack of feeling is at times evident in how little we talk about why we do this work in comparison to our abundant conversations about the technical details of the work.

It’s so easy to become so enamored with the jargon, the politics, and the nuances of our efforts to improve teaching and school quality that we lose sight of the very feelings and inspiration that brought us to this important profession.

But the next frontier of this work is going to require a much wider base of grassroots supporters and as disappointing as it sounds — we’re not going to engage them with a discussion of Title 2a or edTPA or CBAs.

They are going to want to feel our energy and urgency about strengthening the teaching profession.

They are going to want to hear compelling stories about why we invest so much time fighting the fight for equity and excellence at the Capitol and with various school boards.

They are going to want to see that we are not just intellectually invested in our work but that we are also emotionally invested.

I believe we can get there.

We can get there by spending much more time at the grassroots level— By inviting everyday folks into our convenings and conversations and connecting with them where they are.

We can get there by visiting more classrooms, speaking regularly with students, creating opportunities to hear the voices of parents.

The late, great Maya Angelou once said: “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

There are countless advocates and activists waiting to join our efforts to strengthen schools. But we have to be ready to make them feel and be willing to do the same ourselves.